What would Paul Klee say?

Some thoughts on AI and creativity

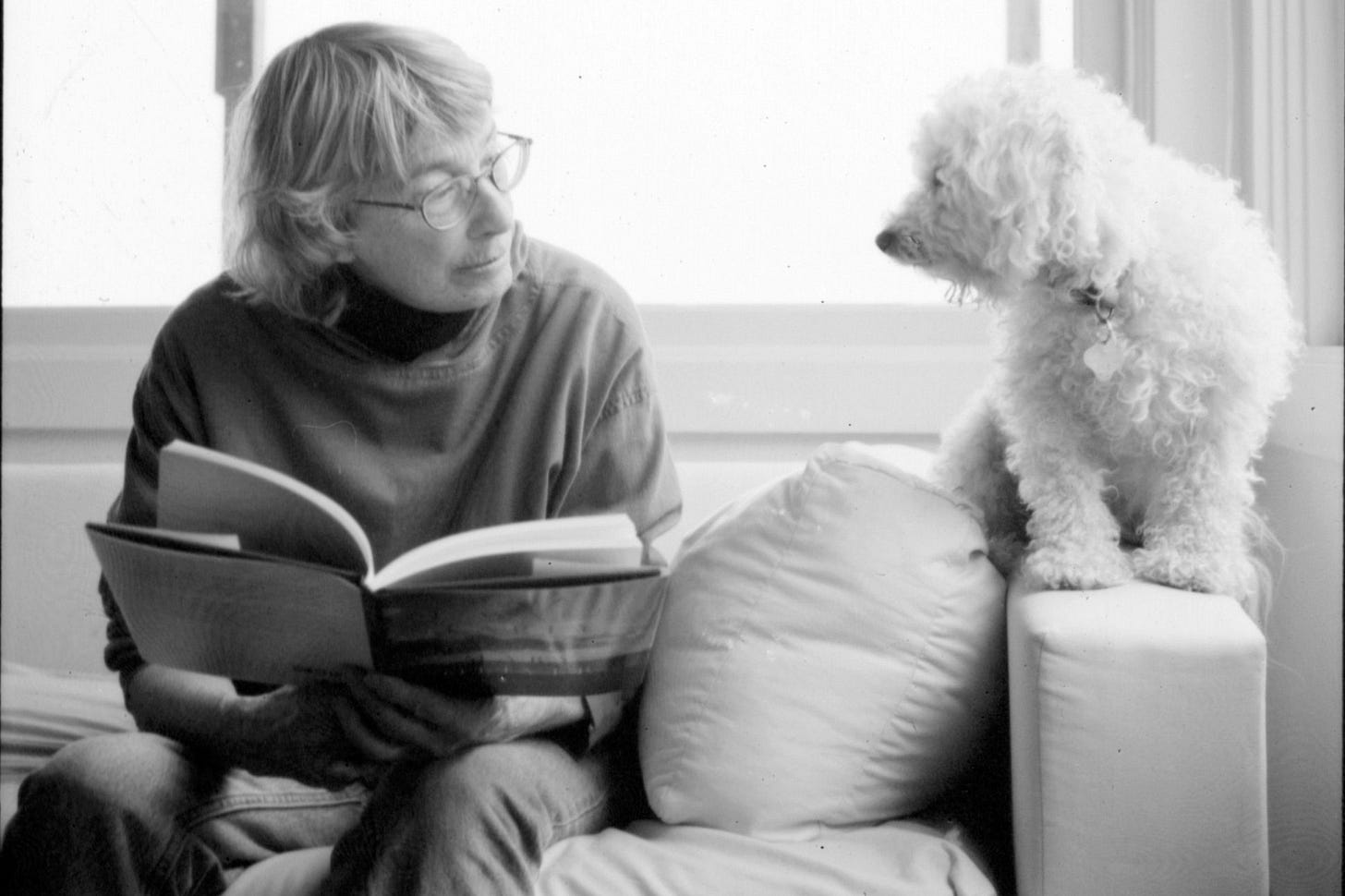

“It is six A.M, and I am working. I am absentminded, reckless, heedless of social obligations, etc. It is as it must be. The tire goes flat, the tooth falls out, and there will be a hundred meals without mustard.” However, as Mary Oliver says, “The poem gets written.” (Oliver, 2016, p.30)

In her essay “Of Power and Time,” Mary Oliver speaks of a force. A supernatural call. A need. An intrinsic motivation bigger than her, greater than her toothache, mustard, or social obligations—“A hunger for eternity” (Oliver, 2016, p.27). The artist does not create out of convenience but out of necessity.

And yet, we now live in an era where AI seems capable of doing anything. From generating images to composing poems and crafting essays, these systems are stepping into realms once thought uniquely human. Consider the case of Jason M. Allen of Pueblo West, Colorado, who entered the Colorado State Fair’s annual art competition. His work, “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial,” won first place in the contest for emerging digital artists. The problem? His piece was not created with brush or paint but with AI.

Jason generated hundreds of images, marveling at their astonishing realism. No matter what he typed, MidJourney delivered: “I felt like it was demonically inspired—like some otherworldly force was involved.”1

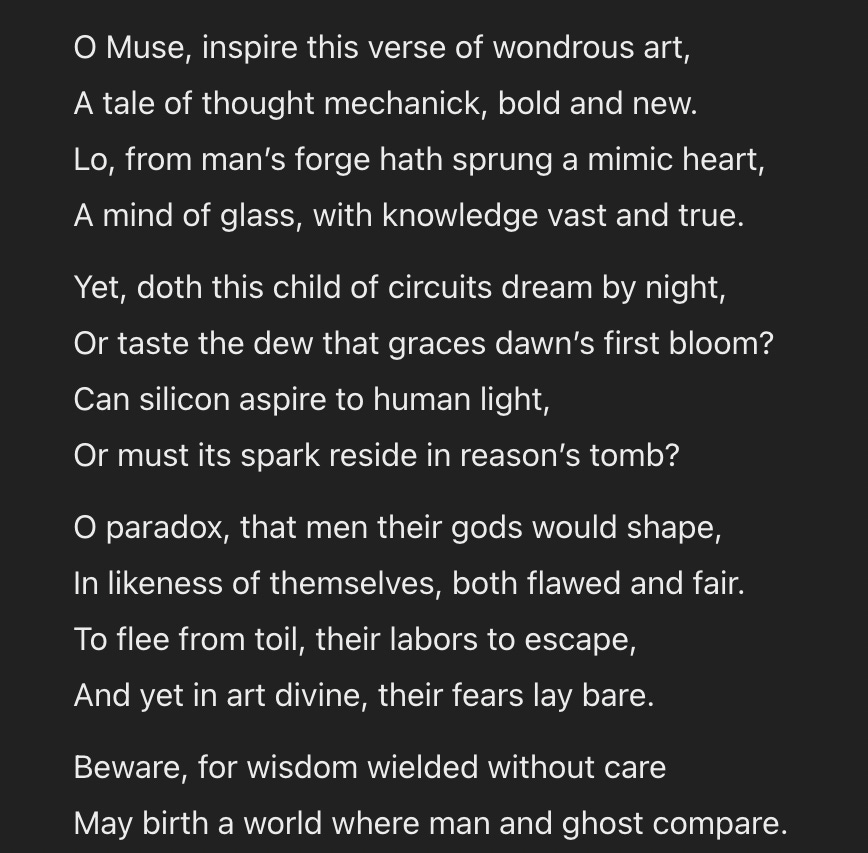

AI does not stop at visual art. Like Mary Oliver, ChatGPT can also write poetry. Ask it to compose a Shakespearean sonnet about artificial intelligence, and it will:

Isn’t this jaw-dropping? The poem is not just structurally sound in its Shakespearean tone (in which I am no expert) but also profound: Does this child of circuits dream by night? Does it taste the dew that graces dawn’s first bloom?

Should one feel amazed? Concerned? Perhaps puzzled?

These systems, trained on the vast corpus of human culture, now compose our novels, craft our poetry, and design our art. Is this… creativity?

On Creativity

By the most widely accepted definitions, the answer appears to be yes. Creativity is often defined as requiring both originality and effectiveness (Runco & Jaeger, 2012). The AI-generated poem is undeniably both—original in its wording and effective in its execution. But is this really what we mean by creativity? Isn’t something missing?

When we assess creativity, we tend to focus on the result: Is this poem creative? Is this image artistic? This output-centered perspective has deep roots in behaviorist tradition, which prioritizes observable outcomes over internal states like beliefs and desires. Behaviorists like B.F. Skinner argued that we don’t need to speculate about what happens inside the mind; instead, we should focus solely on measurable, external behaviors. Intelligence, creativity, even emotion—all inferred from what is done.

This behaviorist legacy profoundly shaped early AI thinking, particularly in the work of Alan Turing. Famously, rather than asking, “Can machines think?” Turing reframed the question in what could be considered a classic behaviorist move: If a machine’s responses are indistinguishable from those of a human, then, for all practical purposes, it can be considered intelligent. This is what Turing said:

We now ask the question, ‘What will happen when a machine takes the part of [the man] in this game?’ Will the interrogator decide wrongly as often when the game is played like this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman? These questions replace our original, ‘Can machines think?’ (Turing, 1959).

But again, isn’t something missing?

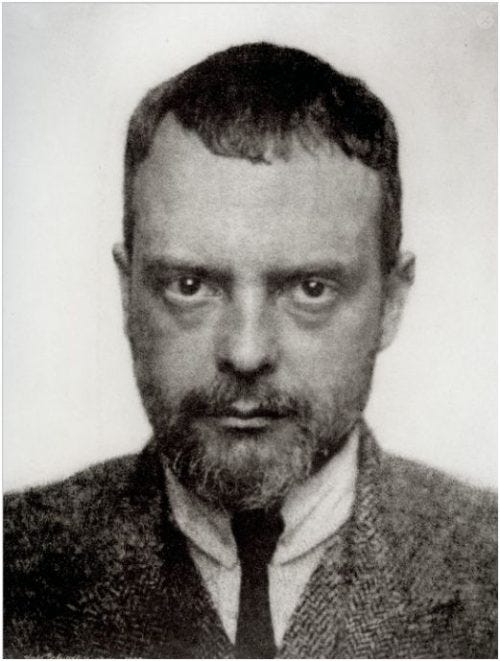

Consider Paul Klee.

Paul Klee and the Formation

Paul Klee (1879–1940) was a Swiss artist closely associated with the Der Blaue Reiter movement in early 20th-century Munich. Though not officially a member, he shared its ethos, rejecting the Impressionists’ external focus in favor of an inward exploration. For artists like Klee and Kandinsky, true art was not merely an arrangement of forms but an expression of an internal necessity—a force.

Kandinsky, much like Mary Oliver, believed in an artistic drive, an inner compulsion that demands expression. A force that obliges us to write that poem, take that picture, use those colors, finish this essay. There will be a hundred meals without mustard, but the poem will get written.

This distinction is crucial when confronting artificial –yet purposeless– systems that generate artistic works. AI can produce images, compose music, and write poetry, but without any need, without any sense of responsibility, without even an understanding of what art is. It has no conception of history, no appreciation for tradition, no hunger for eternity. It does not create because it must, but because it was prompted.

This is not just the difference between humans and AI; it is the fundamental difference between things that are alive and things that are not. As John Dewey observed in his book Experience and Nature (1952):

Empirically speaking, the most obvious difference between living and non-living things is that the activities of the former are characterized by needs, by efforts which are active demands to satisfy needs, and by satisfactions (p.252).

AI acts upon data, but it does not act upon need. It does not yearn. It does not create because it must. And perhaps, therein lies the true essence of creativity: not in the product, but in the process of creating it.

When Klee embraced these ideas about the primacy of mental life in artistic creation, it’s unlikely he was imagining a future in which artificial systems could produce works indistinguishable from those of human artists. Yet, in championing the human way of creating art, Klee and the Expressionists unwittingly drew a line that resonates today, one that remains fundamental:

“The form is bad; the form is the end, it is death.” (Paul Klee, 1924)

This Expressionist perspective aligns closely with contemporary discussions that, in response to AI’s achievements, attempt to redefine creativity by emphasizing the internal, mental processes and cognitive mechanisms that enable creative work. For instance, Mark A. Runco (2023) proposed that human creativity fundamentally involves authenticity and intentionality and that these should be central to our definitions. Moreover, Abraham (2024) underscores the emotional dimension of creativity, highlighting the inherent satisfaction that comes from having a novel or creative idea. This joy, this sense of pleasure in creating something new, may even explain humanity’s drive to produce art (see Aru, 2024). As psychologist Carl Rogers pointed out, “We must face the fact that the individual creates primarily because it is satisfying to him.”

If we truly aim to understand creativity, we must shift our focus from the product to the process. The rise of machine-generated “art” calls for an exploration of the creative experience itself—the subjective, lived reality of creation. Intrinsic motivation, mindfulness, and joy are indispensable aspects of creativity. How is it that the artist did it? What motivated him? Why?

Or, as Alva Noë (2023, p.158) argues, “The thing itself, the made product, has exactly nothing to do with its artistic value.” As Paul Klee would say, the how, not the what, truly matters.

Bibliography

Abraham, A. (2024). Why the standard definition of creativity fails to capture the creative act. Theory & Psychology, 09593543241290232.

Aru, J. (2024). Artificial intelligence and the internal processes of creativity. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.04366

Dewey, J. (1925). Experience and Nature.

Oliver, M. (2017). Upstream: Selected essays. Penguin Press.

Runco, M. A. (2023a). Updating the standard definition of creativity to account for the artificial Creativity of AI. Creativity Research Journal, 1-5.

Runco, M. A. (2023b). AI can only produce artificial creativity. Journal of Creativity, 33(3), 100063.

Noë, A. (2023). The Entanglement: How Art and Philosophy Make Us What We Are. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691239293

Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind, 49, 433–460.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/02/technology/ai-artificial-intelligence-artists.html